One of the recurrent arguments made against the idea of socialism is that it may be good in theory, but in practice it comes up against the rude facts of deeply rooted and unchanging human nature: a nature that is usually typified as selfish, competitive, and acquisitive. Capitalism, it is sometimes argued, exists because it it reflects human nature and, therefore, as Margaret Thatcher used to argue, it is the only game in town, “there is no alternative”. However, whilst humans are capable of being selfish and competitive they can also be altruistic, cooperative and compassionate.

Some socialists have argued that there is in fact, no such thing as human nature, that our nature is malleable and fundamentally determined by our social conditions, that we come into the world as a tabula rasa or blank slate. Louis Althusser, the French structural Marxist, is associated with this view which he derived from his interpretation of Marx’s Sixth Theses on Feuerbach where Marx (1845) stated that the human essence is in reality “the ensemble of the social relations”. Althusser’s views have been hotly contested by other Marxists, not notably, by Geras (1983). Adaner Usmnani also argues that the blank slate theory of human nature is mistaken and that to start from that assumption undermines coherent arguments for socialism.

Required reading

Usamani, A. & Bhaksar, S. (2016). Socialism sounds good in theory, but doesn’t human nature make it impossible to realize? (pp 31-34) In Bhaksar, S. (Ed). The ABCs of Socialism. London: Verso.

In the video talk above Usamani identifies three problem for socialists who assume there is no such thing as a universal human nature.

Firstly, our moral outrage at social injustice flows from a recognition of basic human needs that must be met for human flourishing to exist: needs for such goods as food, shelter, freedom from violence and oppression, and a sense of autonomy. This is not to deny cultural and historical differences between the things that humans value, but it is to appreciate that all humans share basic material and social needs that generate suffering when denied.

Secondly, without the assumption of an underlying human nature that is relatively stable across time, it becomes impossible to interpret, analyse and theorise about the nature of human society or history. If humans are completely blank slates how do we make coherent sense of the reasons for slavery, the sources of inequality or the causes of war. How do we develop workable arguments for social change, or visions of a new kind of social order? Without, some enduring assumptions about a universal human nature, society fragments into a booming, buzzing confusion of unique individuals.

Thirdly, Usamani make a compelling case that the idea of a shared human nature is politically necessary. It is what allows socialists to connect and empathise with working people even when they behave in ways that seems to undermine their own long term interests, like voting for right wing candidates. Usamani argues that unless we understand the underlying concerns that motivate working people, the politics of socialists tends to end up in hopeless, condescending, elitist, finger-wagging, which is no part of mass politics.

The blank slate thesis encourages you to forget that people are always meaningfully animated by certain unshakeable concerns. If we are to win people to our side we have to take these concerns seriously. We have to take their human nature seriously.

Usamani, argues that there is a universal human nature and he accepts that part of that is that people care about themselves and their loved ones, but care of the self and family is not the end of the story.

Humans are capable of many things other than simple selfishness, we are capable of caring for others, we are capable of empathy and compassion, we have the capacity to distinguish fairness from unfairness, and the capacity to hold ourselves to those standards…the bourgeoise view, basically, inflates our selfish drives and ignores these other qualities, socialists do not have to do the same.

Usamani’s final point is that “human nature is always relevant but never decisive”. The way in which society is organised influences the ways in which the drives that constitute our human nature are expressed. A capitalist society, founded on values of competitive individualism and meritocracy, is likely to encourage and enable selfishness and competition. However, a socialist society, one founded on meeting the basic human needs of all, one that values co-operation and equality, is likely to amplify our social and altruistic drives, the better parts of our human nature.

Questions to discuss

- What are the problems for socialist theory if we assume there is no such thing as human nature?

- In what ways does the organisation of capitalist society amplify and mute some aspects of human nature?

- What are the features of a future socialist society that would accentuate the positive and pro-social aspects of human nature?

Additional reading

Graham-Leigh, E. (2018, July). Marxism and human nature. MR Online.

An extract from Thompson, E.P. (1960). Outside the Whale. In Oxford University Socialist Discussion Group (Ed.), Out of Apathy (pp 184-185). London: Verso.

Human nature is neither originally evil nor originally good; it is, in origin, potential. If human nature is what men make history with, then at the same time it is human nature which they make. And human nature is potentially revolutionary; man’s will is not a passive reflection of events, but contains the power to rebel against ‘circumstances’ (or the hitherto prevailing limitations of ‘human nature’) and on that spark to leap the gap to a new field of possibility.

It is the aim of socialism, not to abolish ‘evil’ (which would be a fatuous aim), nor to sublimate the contest between ‘evil’ and ‘good’ into an all-perfect paternal state (whether ‘Marxist’ or Fabian in design), but to end the condition of all previous history whereby the contest has always been rigged against the ‘good’ in the context of an authoritarian or acquisitive society. Socialism is not only one way of organising production; it is also a way of producing ‘human nature’.

Nor is there only one, prescribed and determined, way of making socialist human nature; in building socialism we must discover the way, and discriminate between many alternatives, deriving the authority for our choices not from absolute historicist laws nor from reference to biblical texts but from real human needs and possibilities, disclosed in open, never-ceasing intellectual and moral debate.

The aim is not to create a socialist state, towering above man and upon which his socialist nature depends, but to create an ‘human society or socialised humanity’ where (to adapt the words of More) man, and not money, ‘beareth all the stroke’.

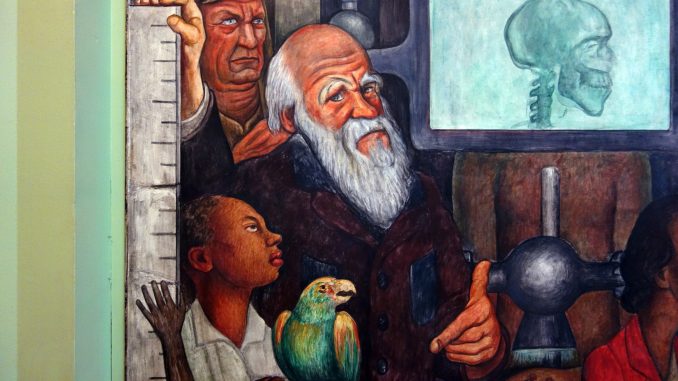

Image credit: Steven Zucker – detail of Man Controller of the Universe, by Diego Rivera (1934) in the Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City